Stress and anxiety

Let’s talk about stress. When I talk about stress, I mostly mean physiological stress, and when I talk about anxiety, I mostly mean the mental health condition. For now.

You would recognise physiological stress by the way your heart rate quickens when you’re under pressure or you need to be alert – it’s a kind of nervous system response. You might also notice anxiety in someone who (among other things) finds it hard to control their worries and fears, particularly about the future.

Learning how to regulate stress

In developmental research, a key question is how we learn to regulate our own stress and emerging emotions. Psychologists think that, in the earlier years, parents help their babies regulate their stress as a team. As the baby gets older and grows towards independence, the child learns gradually to regulate their stress on their own. This makes intuitive sense, but people who work in mental health are often curious about how this works if the parent has a mental health condition – like anxiety.

We did some research looking at this. We wanted to know: do babies match their own stress levels to their anxious parents? Do anxious parents notice, or ‘clock’, when they and their baby are over-stressed, and calm things down? And finally, how do anxious parents respond to moments of stress in their baby – and how does this help the baby recover from stress? We were interested in these questions from a developmental perspective, but you could apply the same sorts of questions to any relationship – like a teacher-pupil dynamic, or a romantic partnership.

Research at home

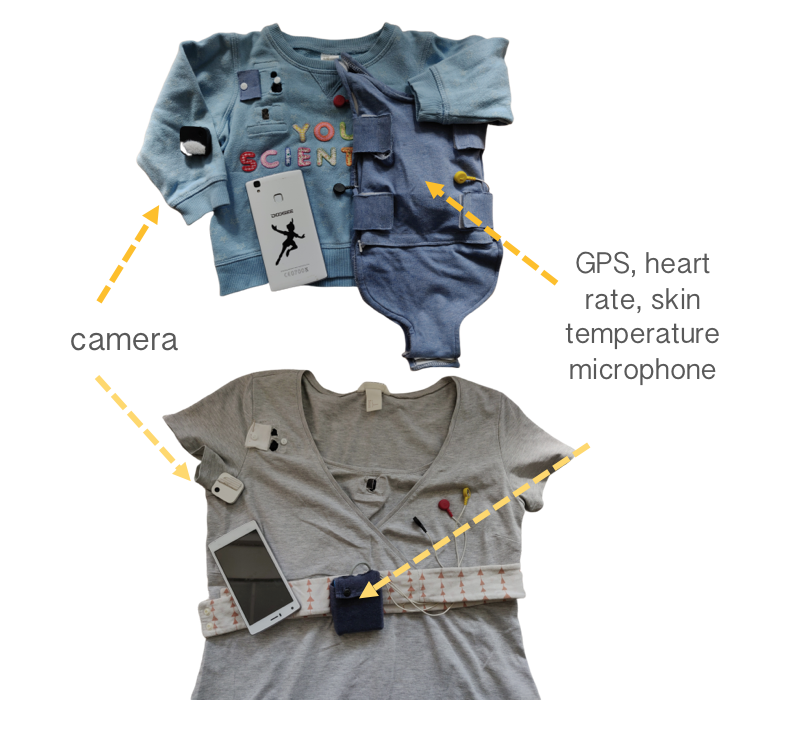

To find out the answers to our question, we ran a study with parents and babies from London, Essex, Hertfordshire and Cambridge. Developmental researchers usually do experiments in the lab, because it can be tightly controlled and we can be confident we are being accurate in our investigations. But we also try, wherever possible, to do research in real world settings. For us to do this, we used miniaturised microphones and heart-rate monitors, which could be worn by parents and babies all day without interruption to their activities. This was so we could continually record stress and speech in families in their homes across the day.

As researchers we try to make sure the people who we work with represent the wider population, if we can. This is why we involved 91 pairs of parents and babies from a big range of social and economic backgrounds. On the other hand, we try to make sure all the babies who are involved are roughly the same age. This is because development can change so much over the first year of life. It would be like comparing apples with oranges, if we were comparing three month old babies with twelve month old ones. In our project, the babies were all about eleven months old. Among the parents, we had a group who had higher levels of anxiety, and a group who didn’t.

Stress mirroring

Our study gave us some interesting information on how parents and babies regulate their stress as a team, when the parent has anxiety. Firstly, we found out that anxious parents and their babies mirrored each other’s stress levels throughout the day, whereas the non-anxious parents and their babies did not. This reflects some other research that has found that:

- anxious parents tend to also have very high coordination of behaviour with their babies

- depressed parents and their babies tend not to be coordinated in behaviour at all, and;

- parents who are neither depressed nor anxious tend to coordinate behaviour with their babies some of, but not all, the time.

We suspect there may be a ‘sweet spot’ of stress mirroring that occurs between parents and babies, but that those of us who are more anxious might overshoot a bit. We don’t quite yet know what this means for the development of child stress regulation – but this is an area a number of researchers are looking into.

Stress clocking

Our project also taught us a little bit about what the parent does when both parent and baby get stressed. We found that, at times like these, non-anxious parents tend to bring down their personal stress levels – as if they have clocked that the stress levels in the relationship are a bit too high, and they are trying to calm everything down. However, we didn’t see this happen in the group of anxious parents and their babies.

It’s important to note here that we do not know if these processes are conscious or voluntary – it’s just the way the parents’ bodies are working. It is interesting though, as perhaps a voluntary ability to clock the collective stress levels in the relationship and actively decrease one’s own stress levels could be a good way of regulating stress. Again, this is something we need to look at more closely.

‘Always on’ versus ‘there when you need me’

The final thing our project told us was about how reactive parents were to their babies when the baby was super stressed out. For this, imagine that you have a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 representing the most stressed you could possibly be, and 1 representing no stress. We found that non-anxious parents would have strong physiological reactions if their babies were super stressed out, at level 10. But if their babies were more moderately stressed – for example, say level 7 or 8, then the parent wouldn’t show a big reaction. The parents were, we might say, ‘there when you need me’.

On the other hand, we found that anxious parents would show a strong reaction if their baby was super stressed out – but they would also show the same reaction whether their baby was only moderately stressed (including levels 9, 8, 7 and so on). So the more anxious parents were sort of on high-alert a lot of the time; they were ‘always on’.

We found this difference interesting as it resembled other research that suggests that anxious parents tend to be more stimulating, vigilant and ‘on’ than non-anxious parents. We also noticed that if parents reacted more selectively to their baby’s stress, then it was more likely that their babies would be quicker at recovering from bad moods in the day.

Final thoughts

We think these findings on stress mirroring, stress clocking, and stress reactivity in anxious parents and their babies are all important for helping us understand more about child development. We especially think they will help us understand more about the development of stress and emotion regulation, and we hope that we can use our findings to help inform support for parents and children who maybe find this harder than others.

If you’re wondering why we didn’t do our study with even more people, that’s a good question. We didn’t have all the resources you need to run a study with thousands of families, but we did make sure we had enough people that we could conduct some meaningful statistical analyses. We would always want to run these projects with bigger groups of people, though, to make sure we can really be confident generalising the findings to the broader population.

It’s also worth noting that our project did not address severe anxiety. We did not work with people with a formal clinical diagnosis of anxiety disorder. Instead, the parents reported their anxiety on a questionnaire. At the moment I am running a study with parents with clinical diagnoses, so hopefully I’ll be able to share more findings from that study in due course.

Children who take part in research are the most remarkable young scientists, and we awarded the babies who helped us with our research a university certificate in gratitude for their hard work. We are deeply grateful to their parents who took part, and who helped us to understand more about stress in children.

This post is adapted for a public audience from the academic paper ‘Anxious parents show higher physiological synchrony with their infants’ (Smith et al., 2021). You can learn more about how to read an academic paper by visiting this blog.