The below interview was conducted for Project Alpha by Professor Tsachi Ein-Dor (Baruch Ivcher School of Psychology) with answers from me, Celia Smith (Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience). The interview relates to the recently published paper available [here]. The transcript of this interview has been translated into Hebrew by the Project Alpha team, and is available to read [here].

- Could you define what parent-child synchrony is and the positive aspects that previous research has found for it?

Parent-child synchrony is a huge topic in developmental research. Professor Ruth Feldman is the scientist I look to for my definition of synchrony. She talks about synchrony as being a timed, coordinated relationship between partners. Synchrony can be concurrent (‘when A is high, B is high’) or sequential (‘changes in A forward-predict changes in B’). I often think about this in terms of biology. So, when my heart rate is high, is my baby’s heart rate high too? Or do changes in my heart rate predict changes in my baby’s heart rate later on? You could also think about how aspects of your behaviour predict changes in your child’s behaviour.

Greater parent-child synchrony is thought to relate to more adaptive cognitive development, school adjustment, and empathy in children. One of the reasons I’m interested in parent-infant synchrony is because it may help us understand how children learn to regulate their own stresses and emotions in their early years.

- In your research, you explored parent-child synchrony throughout the day in an innovative way. Could you explain what you did?

Yes! We were really excited about this methodology, which we developed in contrast to existing methods. Traditionally, research that examines the parent-infant relationship is conducted in a laboratory setting, with a short period of interaction filmed by researchers and then analysed afterwards. Interactions are often given an overall ‘score’ for their synchrony level, and then this is compared with other characteristics of the parent or child. However, this approach doesn’t represent the real world very well.

In the real world, we aren’t watched by scientists while we interact with our infants, and we might behave more naturally as a result. To explore parent-child synchrony in our project, we developed wearable miniaturised monitors that were embedded within clothing so they weren’t obtrusive. These miniature monitors included an ECG machine, a microphone, a GPS tracker, a camera, a movement monitor and a skin temperature detector: all in one. Parents and infants wore these clothes for the day in their homes without the researcher present. We did make sure a privacy function was included in the technology too.

- You have found that anxious parents had were more in sync with their babies, which seems positive. You have found that being “always on” is not entirely positive. Could you explain your finding?

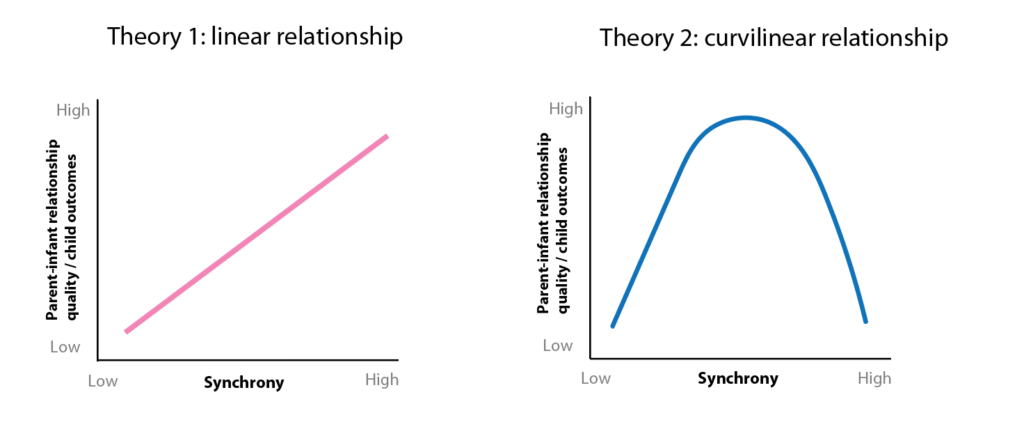

Some developmental researchers believe that the more synchrony between you and your child, the greater the quality of the parent-infant relationship, and the better the child outcomes (let’s call it a ‘linear’ theory). However, others believe that extremes of synchrony (whether too low or too high) indicate a negative context, and that a moderate amount of synchrony is ideal (‘curvilinear’ theory).

My research could be seen to support the second theory. This is because I found that (1) more anxious parents had higher synchrony with their infants compared to less anxious parents and (2) more anxious parents were very reactive to their infants’ distress, even when that level of distress was not particularly high. These findings could be used to support the notion of a hypervigilant parenting style that is sometimes noticed in anxious parents, which can be over-stimulating and over-loading for the child.

I would note, though, that I try to be careful about judging levels of synchrony between parents and children, particularly in contexts where the parent has a mental health condition. We are still learning how levels of synchrony relate to later child development, particularly in the area of emotion regulation.

- What is your take-home message for to-be parents given your findings, and given parents’ wish to be the “best” parents that can possibly be?

My research is still in a very early stage so I would begin by saying that the below information needs to be considered alongside other regulated sources of child development and parenting advice, rather than in isolation.

My take-home message for to-be parents would be: make sure that you are supported to manage your own anxieties, and to maintain an awareness of the ways your anxiety can affect how you behave when you are with others. Notice if you have a tendency to be over-controlling or hypervigilant in your interactions with young children, as this can be a sign of anxiety. If you have a heart rate monitor that you can wear at home, this may help give you feedback on when your stress levels are very high – and you could practice managing these using stress reduction techniques such as paced breathing.

I’m currently working on some research that also looks at how our speech patterns can provoke stress in the parent-child relationship. So, watch this space for more information on how we can use our voice to manage our own and our children’s stress in the future.