In September 2021, I spoke about my PhD research on the intergenerational transmission of stress and anxiety states between parents and infants with Eric W. Dolan, in an interview published for PsyPost. Read the full article here – excerpt below:

***

Mothers with elevated levels of anxiety tend to be more physiologically “in sync” with their infant children, according to new research published in the journal Psychological Medicine. The stress response of less anxious mothers, on the other hand, is less tightly coupled to their infants.

The findings suggest that anxiety symptoms influence how parents and their infants regulate stress, which could have important implications for children’s psychological development.

“I have long been interested in the intergenerational transmission of stress and anxiety states from parent to infant, as well as how emotion dysregulation develops early in life,” said study author Celia Smith, a PhD student at King’s College London. “I’m also incredibly curious about how our experiences of stress seem personally situated and internally regulated – but, in practice, originate from the emotional states of people around us; from our relationships.”

In the study, 68 mothers and their 12-month-old child wore miniature microphones, video cameras, electrocardiograms, and actigraphs at home, which allowed the researchers to measure moment-to-moment fluctuations in arousal in a natural setting. The wearable devices recorded the participants’ heart rate, heart rate variability, physical activity level, and vocalizations. The mothers also completed an assessment of current anxiety symptoms.

“We worked with families from a big range of socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds, which means our research has broad relevance for the general public,” explained Smith. “And we used some innovative research methods in this study that allowed us to work with families in their own homes, without researchers present. This meant we were not restricted to laboratory settings — which are not the best place for measuring authentic stress states — and could make our research more representative of the real world.”

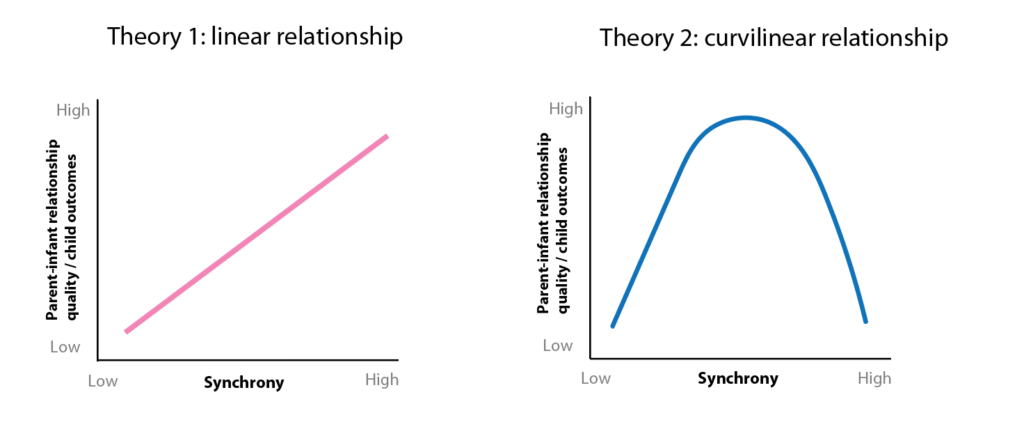

The researchers found that higher levels of maternal anxiety were associated with higher physiological synchrony. In other words, the arousal level of anxious mothers tended to correspond to the arousal level of their infants. Both anxious and non-anxious mothers exhibited physiological reactivity in response to large-scale changes in infant arousal, but anxious mothers also exhibited reactivity to small-scale fluctuations in their infant.

The findings indicate “that stress and anxiety are emotional states that come to be shared and transmitted between individuals, particularly in the context of close parent-infant relationships found in early development. In our study, we show this at the biological level, with anxious parents and infants tending to have very closely matched stress states throughout the day,” Smith told PsyPost.

“We also suggest that parental anxiety plays a role in infant self-regulation. Our study showed that anxious parents are ‘always on’; they tend to physiologically over-respond to minor stress in their infant. This is compared to non-anxious parents, who are ‘there when you need me’; they are only reactive to more extreme infant stress.”

“The parenting style of being ‘always on’ is associated with slower infant recovery from upsetting moments. As anxious parents, we might therefore want to develop greater bodily awareness of our response to infant distress, particularly in relation to how it affects child emotional development,” Smith explained.

The new findings provide insight into the relationship between parental anxiety and parent-infant stress regulation, and provide a basis for future investigations into how parents can best manage anxiety symptoms. But Smith noted that the “findings of this study are only preliminary” at this point.

“We would need to carry out this study with many more families before making any certain claims or recommendations,” she explained. “We also didn’t include parents with severe mental illness in our study, or parents of more diverse genders, and this is something we would want to do in the future to ensure we can generalize to these groups.

“A big question for us, and for future research, is working out how to best support parents with anxiety during the perinatal period, in such a way that we can support both the parent and the infant to thrive,” Smith added.

The study, “Anxious parents show higher physiological synchrony with their infants“, was authored by C. G. Smith, E. J. H. Jones, T. Charman, K. Clackson, F. U. Mirza, and S. V. Wass.